The Maramataka is the traditional Māori lunar calendar that tracks time through the phases of the moon and the position of stars like Matariki. Unlike the solar Gregorian calendar, it dictates the optimal times for planting, fishing, and resting by observing the fluctuating energy levels of the natural environment during specific lunar nights.

For centuries, the indigenous people of Aotearoa (New Zealand) have relied on a sophisticated system of timekeeping that is inextricably linked to the rhythms of the natural world. This system, known as the Maramataka, is far more than a simple method of counting days. It is a comprehensive ecological guide, a predictive tool for survival, and a spiritual framework that connects the people (tangata) to the land (whenua) and the sky (rangi). While the modern world operates largely on the solar Gregorian calendar, there is a significant resurgence in understanding the Māori lunar calendar Matariki connection, particularly as New Zealand embraces Matariki as a public holiday and a time of national reflection.

Understanding the Maramataka requires a shift in perspective—from viewing time as a linear progression of hours to viewing it as a cyclical flow of energy. This guide explores the mechanics of the Maramataka, its critical relationship with the Matariki star cluster, and how you can apply this ancient wisdom to modern gardening and fishing practices.

How does the Maramataka work?

The word Maramataka literally translates to “the moon turning” (marama = moon, taka = to turn or rotate). While the western calendar is solar-based, focusing on the earth’s orbit around the sun (365 days), the Maramataka is lunar-stellar. It is based principally on the 29.5-day cycle of the moon as it waxes and wanes. However, a strictly lunar year is only about 354 days long. To ensure the calendar stays synchronized with the seasons, astronomical markers—specifically the heliacal rising of stars—are used to anchor the lunar months to the solar year.

Each night of the lunar month has a specific name and carries a distinct “energy” or classification. These classifications determine the activities for that day. This is not superstition; it is based on centuries of empirical observation regarding ocean tides, sap flow in trees, animal behavior, and insect activity. The Maramataka is arguably one of the earliest forms of data science employed in the Pacific.

It is important to note that the Maramataka is not uniform across all of New Zealand. Different iwi (tribes) have variations in the names of the nights and the months. This is because the environmental cues in the subtropical Far North differ vastly from those in the alpine regions of the South Island. Localized knowledge (Mātauranga ā-iwi) adjusts the standard framework to fit the specific ecosystem of the hapū (sub-tribe).

The Connection Between the Lunar Calendar and Matariki

The Māori lunar calendar Matariki relationship is foundational to the Māori New Year. The Maramataka does not have a fixed start date like January 1st. Instead, the New Year is triggered by an astronomical event: the reappearance of the star cluster Matariki (the Pleiades) in the pre-dawn sky during the lunar month of Pipiri (June/July).

When Matariki rises, it signals the end of the previous year and the beginning of the new one. However, the exact day of the celebration is determined by the Maramataka. Matariki celebrations typically occur on the first major moon phase following the rising of the stars—often during the Tangaroa phases (last quarter) of the moon. This integration of stellar observation (Matariki) and lunar phases (Maramataka) ensures that the calendar remains aligned with the seasons.

In some regions, particularly the West Coast of the North Island and parts of the South Island where the geography obscures the horizon, the star Puanga (Rigel) is used as the primary marker instead of Matariki. Regardless of the specific star, the principle remains: celestial bodies dictate the reset of the lunar cycle.

Phases of the Moon During Matariki

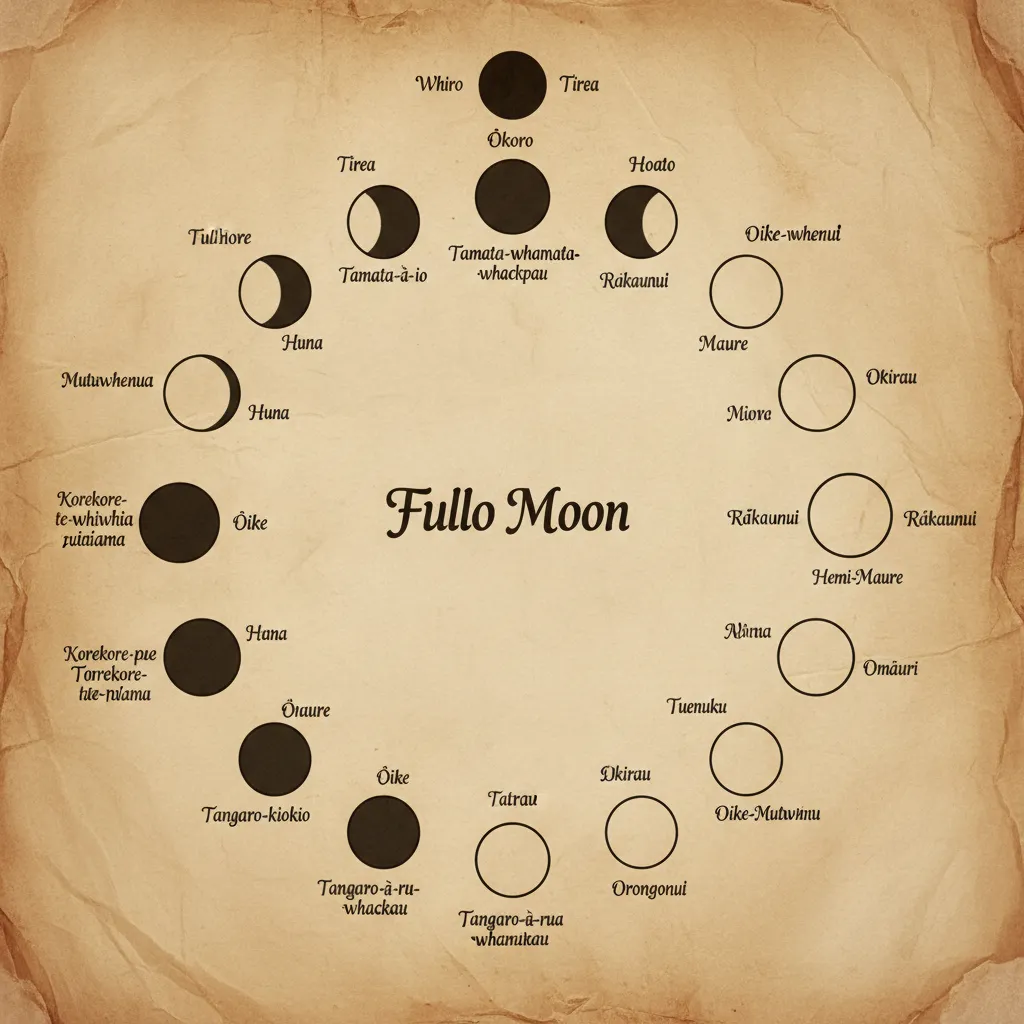

The lunar cycle in the Maramataka is generally divided into roughly 30 nights (though this varies by dialect and region). These nights are grouped into phases that reflect the amount of light the moon provides and the gravitational pull it exerts on the earth. Understanding these groups is essential for interpreting the calendar.

Whiro (New Moon)

The cycle begins with Whiro, the new moon. In Māori tradition, Whiro is often associated with darkness and negative energy. It is considered a time for rest and reflection rather than action. The lack of moonlight makes it a poor time for fishing, and the energy is considered too low for planting. It is a time to retreat and plan for the coming month.

Rakaunui (Full Moon)

At the opposite end of the spectrum is Rakaunui, the full moon. This is a time of high energy and abundance. The sap in trees is running high, making it an excellent time for planting crops that grow above ground. The ocean tides are significant, often bringing activity to marine life. It is a period of productivity and harvest.

The Tangaroa and Tamatea Phases

Between the extremes of the new and full moons lie specific groupings of days that hold particular significance for resource gathering. The most notable of these are the Tangaroa and Tamatea phases.

The Tangaroa Phases

Usually occurring in the days following the full moon (the waning gibbous phase), the Tangaroa nights are highly prized. Tangaroa is the atua (deity) of the ocean. Consequently, these days are considered the premier times for fishing and eeling. The currents are favorable, and fish are believed to be more active and willing to bite. In terms of planting, the Tangaroa phase is often cited as a time of high fertility and growth, excellent for planting root vegetables.

The Tamatea Phases

The Tamatea phases typically occur around the quarter moons. In Māori lore, Tamatea is associated with unpredictability. These days are often characterized by changing winds and volatile weather patterns. The ocean can be rough and dangerous (“Tamatea kai ariki” – Tamatea who devours chiefs). It is generally advised to exercise extreme caution on the water during these days. The energy is unsettled, making it less ideal for planting or starting new major projects. It is a time for vigilance.

Using the Calendar for Fishing and Planting

The practical application of the Maramataka is most visible in mahinga kai (food gathering) and māra kai (gardening). By aligning activities with the moon, practitioners aim to work smarter, not harder.

Fishing (Hī Ika)

The gravitational pull of the moon dictates the tides, which in turn influences the feeding behavior of fish. The Maramataka identifies specific days where the “bite time” is optimized.

- Best Days: The Tangaroa nights (Tangaroa-ā-mua, Tangaroa-ā-roto, Tangaroa-kiokio) are legendary for fishing success.

- Worst Days: The days immediately surrounding the full moon (Rakaunui) can sometimes be too bright for certain species, while the Korekore days (meaning “nothing” or “nil”) are notoriously poor for fishing. On Korekore days, it is said that the fish simply will not bite, and energy is better spent mending nets or maintaining gear.

Planting (Māra Kai)

Gardening by the moon relies on the concept of water tables and sap flow. As the moon waxes (grows), it pulls moisture upwards.

- Waxing Moon (Towards Full): This is the time to plant crops that produce seeds on the outside or grow above ground (e.g., beans, corn, leafy greens). The rising sap encourages strong leaf growth.

- Waning Moon (After Full): As the light decreases, the energy draws down into the roots. This is the optimal time for planting root crops like kūmara (sweet potato), carrots, and potatoes.

- Korekore Days: Similar to fishing, these are days of low productivity. It is best to avoid planting and instead focus on weeding or soil preparation.

Where to buy a Maramataka dial?

With the revival of traditional knowledge, physical Maramataka dials and calendars have become popular educational tools and household items. These dials usually consist of rotating wheels that allow you to match the moon phase with the calendar date, revealing the name of the Māori day and the associated activities.

While many marae and educational institutions provide these resources, there are several commercial options available that support Māori artists and businesses. Purchasing a dial is an excellent way to visually track the lunar cycle and integrate the rhythm of the Maramataka into your daily life.

Recommended sources include:

- Te Papa Store: The Museum of New Zealand often stocks high-quality, educationally accurate Maramataka calendars.

- Local Iwi Websites: Many tribes sell dialect-specific calendars that support local cultural initiatives.

- Māori Bookstores: Retailers specializing in Māori literature often carry Maramataka resources designed for children and adults alike.

Using a Maramataka dial is not just about checking a date; it is about observing the sky. It encourages you to look up, verify the moon’s shape, and reconnect with the environment around you. By syncing your life with the Māori lunar calendar Matariki cycle, you participate in a tradition that has sustained life in Aotearoa for a millennium.

People Also Ask

What are the 30 phases of the Māori moon?

The 30 phases (nights) vary by iwi but generally follow a sequence starting with Whiro (New Moon). Common phases include the Tamatea nights (unpredictable weather), the Tangaroa nights (productive fishing), and Rakaunui (Full Moon). Other phases include the Korekore days (low energy) and the ending phase of Mutuwhenua.

How do you read a Maramataka?

To read a Maramataka, you observe the shape of the moon to identify the current phase (e.g., Full, Quarter, New). You then match this phase to the specific name of the night (e.g., Tangaroa-ā-mua). The name of the night provides instructions on whether it is a good time to fish, plant, or rest.

Is Matariki based on the moon?

Matariki is based on both the stars and the moon. While Matariki is a star cluster (The Pleiades), the timing of the Māori New Year celebration is determined by the lunar calendar. The New Year typically begins on the first new moon or significant phase after the Matariki cluster rises in the pre-dawn sky.

What is the best moon for fishing Māori?

The best moon phases for fishing are generally the Tangaroa phases. These usually occur after the full moon during the waning gibbous stage. The energy of Tangaroa (god of the sea) is strong during these nights, making fish more active and likely to bite.

What are the Tangaroa days?

The Tangaroa days are specific nights in the lunar month dedicated to Tangaroa, the atua of the sea. They are typically Tangaroa-ā-mua, Tangaroa-ā-roto, and Tangaroa-kiokio. These days are renowned for being the most productive times for fishing and eeling.

When does the Māori year start?

The Māori year starts with the first new moon following the heliacal rising of Matariki (or Puanga in some regions) in mid-winter, typically around June or July. This marks the shift from the harvest season to the planting season.