What is Matariki Astronomy?

Matariki astronomy focuses on the heliacal rising of the Pleiades (Messier 45) star cluster in the mid-winter pre-dawn sky of the Southern Hemisphere. In Aotearoa New Zealand, this astronomical event signals the Māori New Year, blending precise celestial mechanics with Mātauranga Māori (traditional knowledge) to mark seasonal shifts, navigation, and environmental planning.

The rising of Matariki is more than a cultural celebration; it is a profound astronomical event that requires specific conditions to observe. For astronomers and photographers alike, capturing this cluster requires an understanding of orbital mechanics, atmospheric conditions, and the interplay between light and darkness. This guide serves as a bridge between the ancestral practice of star gazing and the modern application of astrophotography.

The Science of the Pleiades in the Southern Hemisphere

To photograph Matariki, one must first understand what it is physically. Known in Western astronomy as the Pleiades or Messier 45 (M45), it is an open star cluster located in the constellation of Taurus. It contains over 1,000 confirmed stars, although only a handful are visible to the naked eye. Physically, these stars are hot, luminous, and relatively young—roughly 100 million years old—and are located approximately 444 light-years from Earth.

The Heliacal Rising Explained

The term “Matariki” specifically refers to the cluster’s return to the morning sky. This is known as the heliacal rising. For several months, the cluster is hidden behind the sun. As Earth continues its orbit, the sun moves past the constellation Taurus. Eventually, the stars of Matariki rise above the eastern horizon just long enough to be seen before the sun’s glare washes them out. In New Zealand, this occurs in mid-winter (late June to mid-July).

From an astronomical perspective, the visibility of Matariki is dictated by latitude. The further south you are in Aotearoa, the later the cluster rises. This is why the specific dates for Matariki celebrations can vary slightly between iwi (tribes) in the North and South Islands. The cluster appears low on the northeastern horizon, meaning atmospheric turbulence and light pollution are significant hurdles for clear observation and photography.

How to Locate Matariki: The Anchor Method

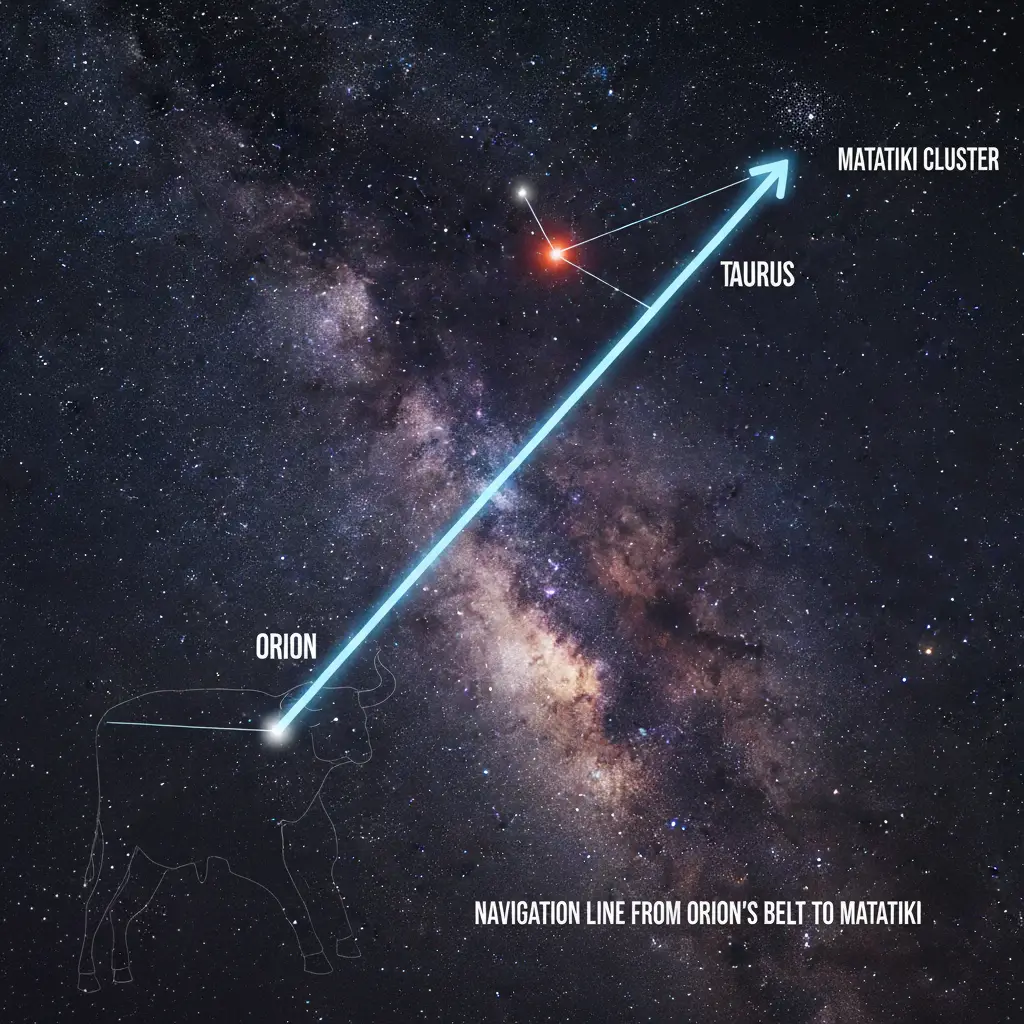

Finding a small cluster of stars in a vast pre-dawn sky can be challenging for beginners. The most reliable way to find Matariki is to use “anchor” constellations that are brighter and easier to identify. This method uses the geometric relationships between prominent celestial bodies.

Step-by-Step Navigation

- Find Tautoru (Orion’s Belt): Look to the northeast between 5:30 AM and 6:30 AM. You will see the distinctive three stars of Orion’s Belt arranged in a straight line. This is the pot’s bottom.

- Trace the Line Leftward: Follow the line of the belt to the left (northward) until you hit a bright orange star. This is Taumata-kuku (Aldebaran), the eye of the Bull in the Taurus constellation. It forms part of a V-shaped cluster called the Hyades.

- Continue the Trajectory: Keep moving your gaze in that same direction, past Taumata-kuku. You will arrive at a tight, twinkling cluster of blue-white stars. That is Matariki.

Unlike the Hyades or Orion, Matariki is very compact. To the naked eye, it looks like a fuzzy smudge or a miniature version of the Little Dipper. Using peripheral vision (looking slightly to the side of the cluster) can often make the individual stars pop out more clearly due to the distribution of rods and cones in the human eye.

Technical Requirements for Night Sky Photography

Applied astronomy through the lens of a camera captures details the human eye cannot resolve. However, the low light environment demands specific gear and a solid understanding of exposure theory.

Essential Gear Checklist

- Camera with Manual Mode: You need full control over ISO, Aperture, and Shutter Speed. A DSLR or Mirrorless camera with a full-frame sensor is ideal for noise performance, but modern crop-sensor cameras are also capable.

- Fast Wide-Angle Lens: You want a lens with a wide aperture (low f-number). An f/2.8 lens is the standard for astrophotography. A focal length between 14mm and 24mm allows you to capture the landscape context along with the stars.

- Sturdy Tripod: This is non-negotiable. Exposures will last between 10 to 30 seconds. Any movement will ruin the shot.

- Remote Shutter or Intervalometer: To avoid shaking the camera when pressing the button. Alternatively, use the camera’s built-in 2-second timer.

- Headlamp with Red Light Mode: Red light preserves your night vision and is less likely to ruin a photo if you accidentally shine it near the lens.

Best Camera Settings for Astrophotography

Photographing Matariki is different from photographing the Milky Way core because the cluster is a distinct object, but the principles of light gathering remain the same. Here is a baseline configuration to start with.

The Exposure Triangle for Stars

1. Aperture (f-stop): Open your lens as wide as it goes (e.g., f/2.8 or f/1.8). This lets in the maximum amount of light. If you find your stars look like comets in the corners (coma), stop down slightly to f/3.2.

2. ISO: This controls the sensor’s sensitivity to light. Start at ISO 1600 or 3200. While higher ISOs introduce digital noise, modern noise reduction software is very effective. It is better to have a noisy shot with sharp stars than a clean shot with blurry stars.

3. Shutter Speed (The 500 Rule): Because the Earth rotates, stars will appear to trail if the shutter is open too long. To get pinpoint stars, use the “500 Rule”: Divide 500 by your focal length.

Example: 500 / 24mm lens = 20.8 seconds. Set your shutter speed to 20 seconds. If you are using a crop sensor, multiply your focal length by the crop factor (1.5x or 1.6x) before dividing.

Focusing in the Dark

Autofocus will not work on the night sky. You must use manual focus. Turn on “Live View” and digitally zoom in on the brightest star you can find (Sirius or Canopus are good options). Rotate the focus ring until the star is as small and sharp as possible. Once focused, use gaffer tape to secure the focus ring so it doesn’t move.

Best Locations for Low Light Pollution in NZ

To see the seven (or nine) stars of Matariki clearly, you need to escape light pollution. New Zealand is home to some of the darkest skies on the planet, offering world-class astrophotography opportunities.

Aoraki Mackenzie International Dark Sky Reserve

Located in the South Island, this is the gold standard for astronomy in New Zealand. The region, including Lake Tekapo, Mt Cook, and Twizel, has strict lighting ordinances. The foreground of the Southern Alps provides a majestic scale against the rising cluster.

Great Barrier Island (Aotea)

As an International Dark Sky Sanctuary, Aotea offers an island perspective. Being off the grid and far from Auckland’s light dome, the eastern beaches (like Medlands Beach) provide an unobstructed view of the horizon where Matariki rises over the ocean.

Stewart Island (Rakiura)

Rakiura literally translates to “The Land of Glowing Skies.” Being the southernmost populated island, it offers long winter nights. While the aurora australis is the main attraction here, the lack of pollution makes star clustering incredibly sharp.

Wairarapa Dark Sky Reserve

For those in the North Island closer to Wellington, the Wairarapa region has recently been accredited. Locations like Castlepoint offer dramatic limestone reefs as foreground elements for your Matariki composition.

Using Technology to Bridge Traditional Knowledge

Modern technology does not replace Mātauranga Māori; rather, it validates the precision of ancestral observation. We can use apps to plan our shoots and confirm our sightings, bridging the gap between ancient navigation and digital imaging.

Recommended Apps

- Stellarium Mobile: This is a planetarium in your pocket. You can fast-forward time to see exactly where and when Matariki will breach the horizon at your specific GPS location.

- PhotoPills: The ultimate tool for photographers. Its “Night AR” mode allows you to hold your phone up and visualize the path of the stars, helping you align the cluster with landscape features like a mountain peak or a specific tree.

- Matariki specific apps: Several NZ-developed apps focus specifically on the cultural context, helping users identify the individual stars within the cluster (Waitī, Waitā, Waipuna-ā-rangi, Tupu-ā-nuku, Tupu-ā-rangi, Ururangi, Pōhutukawa, Hiwa-i-te-rangi) and their associated domains.

By using these tools, you are engaging in “Applied Astronomy”—using data to execute a precise observation. When you capture that image, you are documenting a celestial event that has guided people in Aotearoa for centuries.

People Also Ask

When is the best time to photograph Matariki?

The best time is during the mid-winter months of June and July, specifically in the pre-dawn hours between 5:30 AM and 6:30 AM, just before the sun begins to brighten the sky.

What direction should I look to find Matariki?

You should look towards the northeast horizon. If you can locate Orion’s Belt, follow the line to the left through the triangular face of Taurus to find the cluster.

Can I photograph Matariki with a smartphone?

Yes, if your smartphone has a “Night Mode” or “Pro Mode” that allows for long exposures (10-30 seconds) and you use a tripod or stable surface to prevent shake.

Why does Matariki disappear from the sky?

Matariki disappears because of the Earth’s orbit around the Sun. For a period, the sun is positioned between Earth and the cluster, making the stars invisible due to the sun’s glare (solar conjunction).

How many stars are in the Matariki cluster?

Astronomically, there are over 1,000 stars. Culturally, most people identify 7 stars, but in many Māori traditions, there are 9 visible stars, each with specific environmental associations.

What is the difference between Matariki and the Pleiades?

They are the same physical star cluster (M45). “Pleiades” is the Greek name used in Western astronomy, while “Matariki” is the Māori name, which carries specific cultural, spiritual, and seasonal significance for New Zealand.