Matariki lesson plans for the NZ curriculum are structured educational units designed to teach primary students about the Māori New Year. These plans integrate social sciences, science, and the arts, focusing on the history of the star cluster, traditional navigation, remembrance of ancestors, and setting aspirations for the year ahead through culturally responsive pedagogy.

The Significance of Matariki in New Zealand Schools

Integrating Matariki into the primary classroom is more than just marking a public holiday; it is a vital opportunity to connect ākonga (students) with the indigenous knowledge systems of Aotearoa. As the New Zealand Curriculum refreshes with Te Mātaiaho, the emphasis on Aotearoa New Zealand’s histories and local curriculum design makes Matariki a cornerstone event. It offers a unique cross-curricular opportunity to explore science, history, arts, and literacy through a Te Ao Māori lens, often referencing 25 Matariki Quotes: Inspiring Words for Reflection, Growth, and Cultural Celebration”.

Matariki is a time for three primary actions: remembering those who have passed (remembrance), celebrating the present harvest (celebrating), and looking forward to the future (aspiration). Effective Matariki lesson plans NZ curriculum aligned strategies should weave these three threads into every activity, ensuring that students understand the holistic nature of the celebration. By doing so, educators foster a deeper sense of belonging and cultural identity among all students, regardless of their background.

Unit Plan: The History of the Holiday

This unit focuses on the Social Sciences and Aotearoa New Zealand’s Histories curriculum areas. The goal is for students to understand why the appearance of the Pleiades star cluster signals the New Year and how this tradition has evolved.

What is the Legend of Matariki?

Begin the unit by exploring the purākau (legends) associated with the stars. In many traditions, Matariki is the mother surrounded by her daughters (Tupu-ā-nuku, Tupu-ā-rangi, Waipuna-ā-rangi, Waitī, Waitā, and Ururangi). In other iwi variations, there are nine stars, including Pōhutukawa and Hiwa-i-te-rangi. Teaching these variations is crucial for showing students that mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) is diverse and iwi-specific.

Lesson Activity: The Timeline of Recognition

Create a timeline activity that helps students visualize the history of Matariki. Start with the pre-colonial era where the stars dictated planting and harvesting. Move through the colonization period where these traditions were suppressed or lessened, and conclude with the modern revitalization movement, leading to the first public holiday in 2022. This meets the curriculum requirement of understanding how the past shapes our present.

- Junior Primary (Years 1-3): Focus on the names of the stars and their domains (e.g., Tupu-ā-nuku is for food in the ground). Use flashcards and matching games.

- Senior Primary (Years 4-8): Investigate the specific environmental indicators associated with each star. For example, how Waitā connects to the ocean and tides.

Science Module: Astronomy and Navigation

The science of Matariki provides a tangible connection to the physical world, blending western astronomy with traditional ocean navigation.

How did Māori use stars for navigation?

Polynesian navigators were master astronomers. They used the rising and setting of stars, including the Matariki cluster, to navigate the vast Pacific Ocean. This module should teach students about the cardinal directions and how the night sky acts as a map.

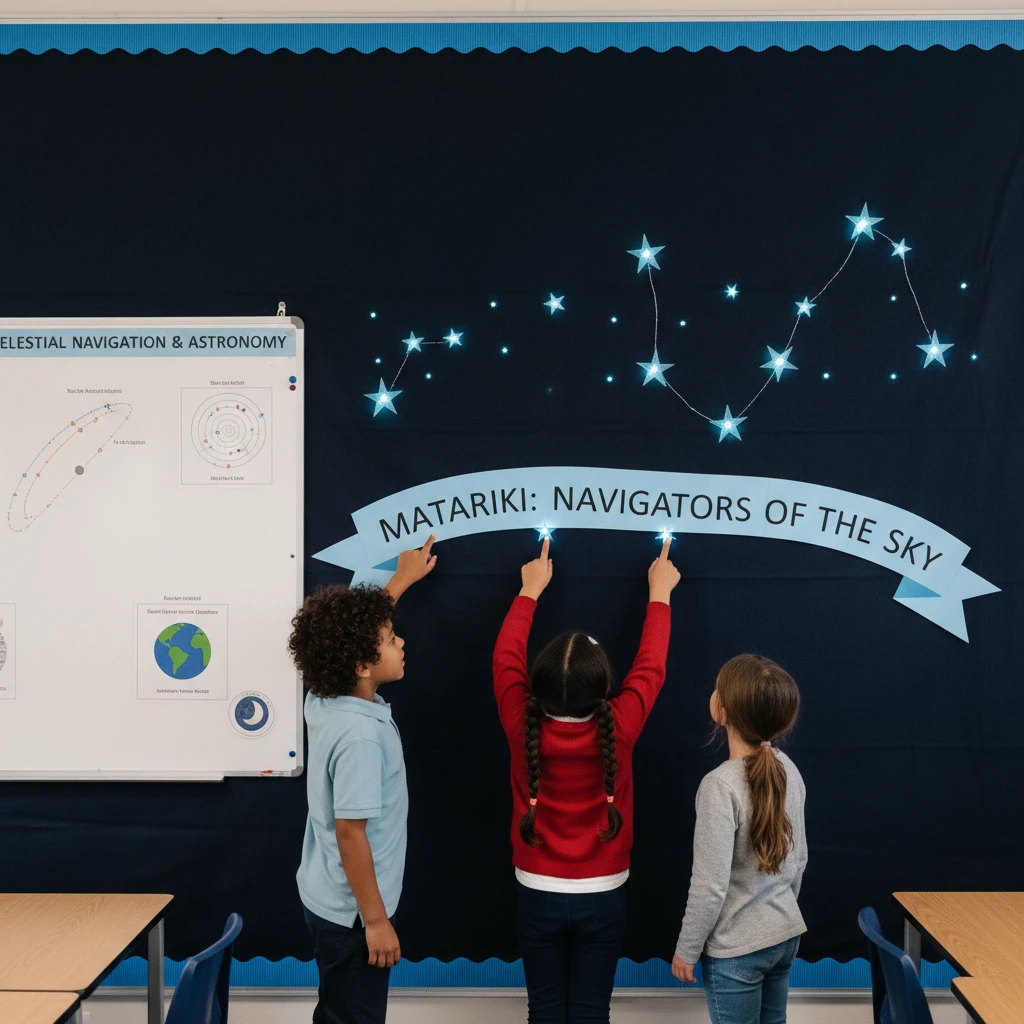

Lesson Activity: Mapping the Night Sky

Objective: Students will identify the Matariki cluster (Pleiades) and understand its position relative to the horizon.

Materials: Black construction paper, white chalk or paint, and tools like the Interactive Night Sky Map Tool: Locate Matariki Now.

Procedure:

1. Explain that Matariki appears low on the northeast horizon in mid-winter just before dawn.

2. Have students create their own star compasses.

3. Discuss the concept of heliacal rising (the first time a star becomes visible in the eastern sky before sunrise).

For senior students, expand this into the ‘Science – Planet Earth and Beyond’ strand. Discuss the life cycle of stars and why the cluster is blue (indicating young, hot stars). Compare the Māori lunar calendar (Maramataka) with the Gregorian solar calendar to explain why the date of Matariki shifts every year.

Art Project: Creating a Manu Tukutuku (Kite)

Kite flying is a traditional Māori practice, particularly during Matariki. Manu tukutuku were flown to connect the heavens (Ranginui) and the earth (Papatūānuku). They were often used to send messages to people who had passed away.

Why do we fly kites during Matariki?

Flying kites symbolizes the spiritual connection between the physical world and the spiritual realm. It is a time to release burdens and send wishes up to the stars. From an arts curriculum perspective, this project covers structural design, cultural symbolism, and the use of sustainable materials.

Step-by-Step Manu Tukutuku Lesson

Materials Needed:

Toetoe stalks, raupō, or flax (harakeke) are traditional, but for general classrooms, use bamboo skewers, lightweight paper or fabric, string, and feathers.

Instructions:

1. Design: Have students sketch their kite designs. Encourage them to include patterns that represent their family or local geography (maunga/mountains, awa/rivers).

2. Frame Construction: Lash the sticks together to form the frame. The most common shape is the ‘manu’ (bird) or a simple diamond.

3. Covering: Attach the paper or fabric. This is where students can paint their designs.

4. The Tail: Explain that the tail provides stability (science connection: aerodynamics). Decorate with feathers or woven flax strips.

5. Flying: Take the class outside on a day to fly their creations. This physical activity reinforces the concept of ‘hau’ (wind/breath of life).

Writing Prompts: ‘My Wishes for the Year’

This literacy module connects to the star Hiwa-i-te-rangi. This is the star to which Māori would send their wishes and aspirations for the coming year. It aligns with the ‘aspiration’ theme of Matariki.

How to structure the writing activity?

Move beyond simple wish lists. Encourage students to think about ‘manakitanga’ (kindness/generosity) and personal growth. The writing should reflect goals that help not just the individual, but their whānau (family) and community.

Differentiated Prompts

Level 1-2 (Junior):

“If I could catch a star, I would wish for…”

“This year, I want to learn how to…”

“I can help my family by…”

Level 3-4 (Senior):

“Hiwa-i-te-rangi represents our future aspirations. Write a letter to your future self at the end of the school year. What do you hope to have achieved?”

“Matariki is a time for resetting. Describe a habit you want to leave behind and a new positive habit you want to start.”

“How can the values of Matariki (remembrance, celebrating, looking forward) help us build a better school community?”

Integrating Te Reo Māori and Tikanga

No Matariki unit is complete without the integration of Te Reo Māori. Language is the vehicle of culture. Teachers should aim to normalize the pronunciation of the star names and associated vocabulary.

Essential Vocabulary (Kupu Hou)

- Whetū: Star

- Hākari: Feast/Celebration

- Whānau: Family

- Kai: Food

- Hauhake: Harvest

- Maumahara: Remember

Incorporate waiata (songs) about Matariki into your morning circle time. Songs like “Ngā Tamariki o Matariki” are excellent for memorizing the names of the stars. Furthermore, ensure that tikanga (protocol) is observed when working with natural materials or food, reinforcing respect for the environment and resources.

People Also Ask (PAA)

What are the 9 stars of Matariki?

The nine stars generally recognized in the Matariki cluster are: Matariki (the mother), Pōhutukawa, Tupu-ā-nuku, Tupu-ā-rangi, Waipuna-ā-rangi, Waitī, Waitā, Ururangi, and Hiwa-i-te-rangi. Each star holds a specific domain, such as fresh water, salt water, winds, or food grown in the ground.

How do you explain Matariki to a child?

Matariki can be explained to a child as the Māori New Year. It is a special time when a group of stars rises in the winter sky. It signals a time to gather with family, remember loved ones who have passed away, give thanks for our food, and make wishes for the year ahead.

What activities are done during Matariki?

Common activities include shared feasts (hākari) at the Best Restaurants for Matariki, storytelling regarding ancestors and legends, flying kites (manu tukutuku), planting trees or crops, singing waiata, and learning about the stars and navigation. In schools, this often involves art projects and goal-setting exercises.

Why is Matariki important in the NZ curriculum?

Matariki is important because it acknowledges the indigenous history and knowledge of Aotearoa New Zealand. It provides a meaningful context for learning about science (astronomy), social sciences (history and culture), and the arts, while fostering national identity and bicultural understanding.

What is the story behind Matariki?

The most common story is that Matariki is the mother star surrounded by her daughters. They journey across the sky to visit their grandmother, Papatūānuku (Earth Mother). Another legend involves the god Tāwhirimātea, who, in anger at the separation of his parents, tore out his eyes and threw them into the sky, creating the cluster (‘Ngā Mata o te Ariki’ – The Eyes of the God).

When should schools celebrate Matariki?

Schools should celebrate Matariki in June or July, aligning with the heliacal rising of the star cluster. The specific dates change annually based on the lunar calendar (Maramataka). It is best to plan unit studies leading up to the official public holiday to maximize student engagement.