Traditional Māori food preservation relies on ingenious techniques like sun-drying (pāwhara), fermentation (kōpiro), and fat-rendering (huahua) to ensure survival during Aotearoa’s cold winters. These methods, combined with sophisticated underground storage pits (rua) for crops, demonstrate a profound understanding of microbiology and environmental resource management.

For early Māori, the ability to preserve *kai* (food) was not merely a culinary preference; it was the difference between life and death. Arriving in Aotearoa from the tropical Pacific, ancestors had to rapidly adapt their horticultural and preservation practices to a temperate climate with distinct, harsh winters. The result was a sophisticated system of food technologies that allowed *iwi* (tribes) to sustain large populations, host lavish *hākari* (feasts), and maintain *mana* (prestige) through hospitality.

What are the traditional drying techniques for fish and eels?

Drying was perhaps the most ubiquitous form of traditional Māori food preservation, particularly for coastal tribes and those situated near major waterways like the Waikato River or Lake Taupō. The process, known generally as *pāwhara* or *makamaka* depending on the specific method and dialect, relied on the natural elements of sun and wind to remove moisture, thereby inhibiting bacterial growth.

The Process of Pāwhara

The preparation of *ika* (fish) and *tuna* (eels) was a communal activity governed by strict protocols. The fish were first gutted and split open. For larger species like shark (*mangō*) or school shark, the flesh might be cut into strips. These were then hung on *whata*—elevated stages or racks—to dry.

The location of the *whata* was critical. It needed to be in an area with maximum airflow but protected from rain. In some instances, a small, smoky fire was lit beneath the racks. Unlike modern hot smoking which cooks the food, this was often a cold smoke designed to deter flies and add a layer of chemical preservation through the smoke compounds.

Preserving Tuna (Eels)

Eels were a staple protein source. During the *heke* (migration), eels were caught in vast numbers. To preserve them for winter:

- Splitting: The eels were split down the backbone, keeping the skin intact.

- Removing the backbone: This facilitated faster drying.

- Hanging: They were hung on poles, often for weeks, until they became hard and leathery.

Once fully dried, these eels could be stored for months. To eat them, they would be softened by steaming in a hāngī (earth oven) or boiling, reconstituting the flesh into a nutrient-dense meal.

How did Māori utilize fermentation for preservation?

Fermentation is a biological process that converts sugars into acids, gases, or alcohol. Māori mastered this technique, known as *kōpiro*, to preserve food and create distinct flavor profiles that are still prized by elders today. This controlled spoilage prevented harmful pathogens from taking hold while softening tough fibers.

Kānga Wai (Fermented Corn)

While corn (*kānga*) was introduced by Europeans, Māori quickly adapted it into their preservation repertoire, creating *kānga wai* or *kānga pirau* (rotten corn). This became a staple “traditional” food in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The process involves:

- Selection: The corn cobs are gathered, leaving the husks on.

- Submersion: The cobs are placed in sacks and submerged in a clean, running stream (*wai*) for several weeks to three months.

- Fermentation: The running water washes away the starch while bacteria ferment the kernels, turning them soft and creating a strong, pungent aroma.

- Cooking: The kernels are mashed and boiled into a porridge, often served with cream and sugar today.

Kōura (Crayfish) and Kina

Freshwater crayfish (*kōura*) were also fermented. They were submerged in swamp water or streams until the shells became soft and the meat took on a cheesy, fermented consistency. Similarly, *kina* (sea urchin) could be preserved in their own juices in a process that intensified their savory, oceanic flavor. This method allowed protein to be stored without the need for drying, providing a softer texture for consumption.

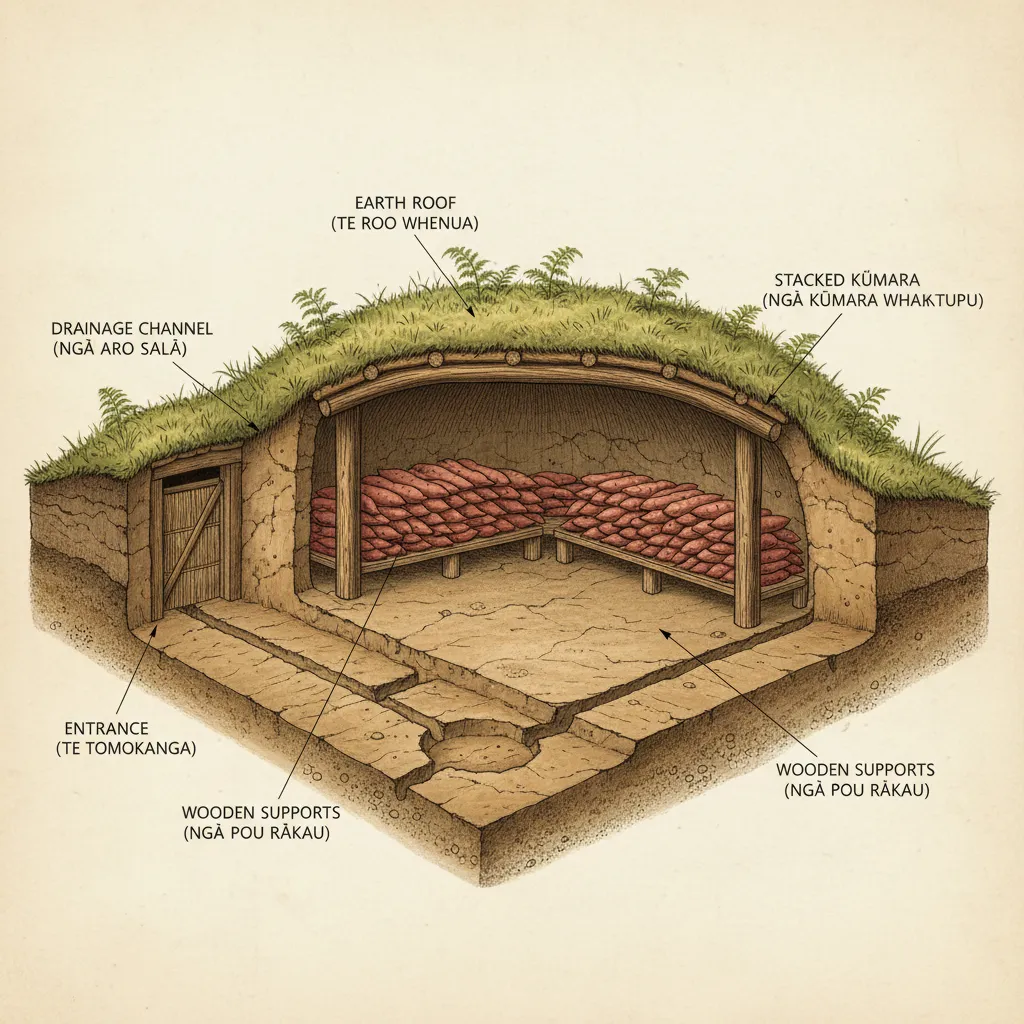

What is the engineering behind Rua Kūmara?

The *kūmara* (sweet potato) is a tropical plant that struggles in New Zealand’s frost-prone winters. To ensure the tubers survived from harvest (autumn) through to planting (spring) and consumption (winter), Māori developed highly sophisticated underground storage pits called *rua kūmara*.

Temperature and Humidity Control

The *rua* acted as a climate-controlled root cellar. If the temperature dropped too low, the tubers would rot from frost; if too high, they would sprout or desiccate. The earth provided insulation, maintaining a stable temperature between 13°C and 16°C.

Structural Design

Archaeological evidence shows various designs, from bell-shaped pits to semi-subterranean rectangular houses. Key engineering features included:

- Location: Built on slopes or ridges to ensure water runoff.

- Drainage: Internal drains and soak holes were dug to prevent water pooling.

- Fumigation: Before loading the crop, the pits were often fumigated with burning herbs (like *kawakawa*) to kill fungal spores and insects.

- Sealing: The entrance was tightly sealed with a wooden slab and buried to maintain the internal atmosphere.

How was fat used to preserve birds (Huahua)?

One of the most prestigious forms of traditional Māori food preservation was *huahua*—the preservation of game birds in their own rendered fat. This method is comparable to the French *confit* and was reserved for high-value species like the *kererū* (wood pigeon), *tītī* (muttonbird), and *kākā*.

The Process of Tahū

The process began with the snaring of birds when they were at their fattest, typically after feasting on seasonal berries. The bones were carefully removed (a process called *makiri*), and the flesh was cooked in wooden bowls using red-hot stones to render the fat.

Once cooked, the birds were packed tightly into vessels. The rendered fat was poured over them, creating an airtight seal that prevented oxidation and bacterial spoilage. If the fat layer remained unbroken, the meat could last for a year or more.

Vessels: Taha and Pātua

The containers used for *huahua* were works of art in themselves:

- Taha: Large calabash gourds, often fitted with carved wooden mouthpieces (*ngutu*) and placed in woven baskets for support.

- Pātua: Vessels made from totara bark, used for larger quantities or transport.

Serving *huahua* to guests was a sign of immense respect and high status, as it represented the culmination of significant labor and resource management.

How are these preservation methods adapted today?

While modern technology like deep freezers and vacuum sealers has replaced the survival necessity of these techniques, the cultural practice of traditional Māori food preservation remains alive, adapted for contemporary convenience while maintaining the spirit of the tradition.

From Whata to Smokehouse

The open-air *whata* has largely been replaced by the backyard smokehouse. Manuka sawdust is still the preferred fuel, imparting that distinct, sweet-savory flavor to fish and eels. However, modern smokers often utilize hot smoking (cooking while smoking) rather than the traditional cold smoke drying, meaning the product must be refrigerated rather than stored at ambient temperatures.

Contemporary Fermentation

*Kānga wai* is still prepared in rural communities and on marae, though plastic drums have replaced woven flax kits, and the fermentation process is often monitored more closely for food safety standards. The taste remains a polarizing but beloved marker of identity for many Māori.

The Tītī Trade

The preservation of *tītī* (muttonbirds) continues as a major cultural industry, particularly for Rakiura (Stewart Island) Māori. While the birds are now often salted and packed in plastic buckets rather than kelp bags (*pōhā*) and fat, the rights to harvest and the transfer of knowledge regarding the bird’s lifecycle remain staunchly traditional.

Why is preserving kai vital to Māori identity?

Preserving kai is about more than nutrition; it is an expression of *kaitiakitanga* (guardianship) and *manaakitanga* (hospitality). The ability to open a storehouse and feed guests with preserved delicacies during the lean winter months was a powerful demonstration of a tribe’s wealth, organization, and harmony with their environment.

Today, reviving and maintaining these practices is a form of cultural resistance and education. It reconnects young Māori with the maramataka (lunar calendar) and the seasonal rhythms of the natural world, ensuring that the knowledge of the ancestors is not lost to the convenience of the supermarket.

What foods did Māori traditionally preserve?

Māori traditionally preserved a wide variety of foods including seafood (fish, eels, crayfish, shellfish), birds (kererū, tītī), and root crops (kūmara, taro). They also fermented berries and later, corn.

How did Māori store kūmara for winter?

Māori stored kūmara in rua (pits) dug into the earth. These pits were engineered for drainage and temperature control, keeping the tubers cool, dark, and dry to prevent rotting or sprouting.

What is the Māori method of preserving birds in fat?

This method is called huahua. Birds were cooked, deboned, and packed into gourds (taha) or bark containers. Rendered fat was poured over them to create an air-tight seal, preserving the meat for months.

What is rotten corn (Kānga Wai)?

Kānga wai is corn that has been fermented by submerging sacks of corn cobs in running water for several weeks. The kernels ferment, becoming soft and developing a strong, sour flavor before being mashed and boiled.

Did Māori use salt for preservation?

Traditionally, Māori did not use salt for preservation before European contact. They relied on drying (sun and wind), smoking, fermentation, and sealing in fat to preserve food.

What is a whata?

A whata is an elevated storage platform or rack used by Māori to dry food (like fish) and store crops above the ground, protecting them from dampness and pests like rats.