Matariki is the Māori name for the Pleiades star cluster, and its origin story is rooted in the separation of Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother). In a fit of grief and rage, the god of wind, Tāwhirimātea, tore out his own eyes and crushed them into the sky, creating “Ngā Mata o te Ariki Tāwhirimātea” (The Eyes of the God Tāwhirimātea), or Matariki.

The Astronomical History of the Cluster

While the Matariki origin story for adults often focuses on mythology, it is impossible to separate the narrative from the hard science of astronomy. Matariki is known internationally as the Pleiades (Messier 45), an open star cluster located in the constellation Taurus. It is one of the nearest star clusters to Earth and arguably the most obvious to the naked eye in the night sky.

For the ancestors of the Māori, the Polynesians who navigated the vast Pacific Ocean, this cluster was not merely a pretty arrangement of lights; it was a critical navigational beacon and a seasonal marker. The rising of Matariki on the northeastern horizon in mid-winter (typically late June or early July) signals the start of the Māori New Year. However, the astronomical history goes deeper than simple observation.

Historically, the visibility of these stars was a matter of survival. The pre-colonial Māori tohunga kōkōrangi (expert astronomers) would observe the cluster intently before sunrise. They were not looking just for the presence of the stars, but analyzing their clarity, brightness, and distance from one another. Atmospheric disturbances affecting the view of the cluster were interpreted as predictors for the coming season’s weather, crop yield, and fishing success. This blends the origin story with practical, empirical science—a nuance often lost in simplified explanations.

The Cosmological Origin: Tāwhirimātea’s Rage

To truly understand the Matariki origin story for adults, one must look to the Māori creation narratives (pūrākau). The most prevalent tradition regarding the creation of the cluster links directly to the separation of Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother).

In the beginning, Rangi and Papa were locked in a tight embrace, leaving their children in darkness. The children, who were the atua (gods) of the natural world, conspired to separate their parents to let light into the world. Tāne Mahuta (god of forests) eventually succeeded in pushing them apart. However, not all the brothers agreed with this course of action.

What does “Ngā Mata o te Ariki” mean?

Tāwhirimātea, the god of wind and storms, was devastated by the separation of his parents. In his profound grief and anger, he waged war against his brothers. As a final act of defiance and mourning, Tāwhirimātea tore out his own eyes, crushed them in his hands, and threw them into the heavens to stick onto his father’s chest (the sky).

This act created the star cluster. The name “Matariki” is widely accepted as a truncation of the full phrase: “Ngā Mata o te Ariki Tāwhirimātea”—The Eyes of the God Tāwhirimātea. This narrative provides a somber, mature context to the holiday. It reminds us that the New Year is not just about celebration, but also about acknowledging grief, remembrance, and the cyclical nature of conflict and resolution.

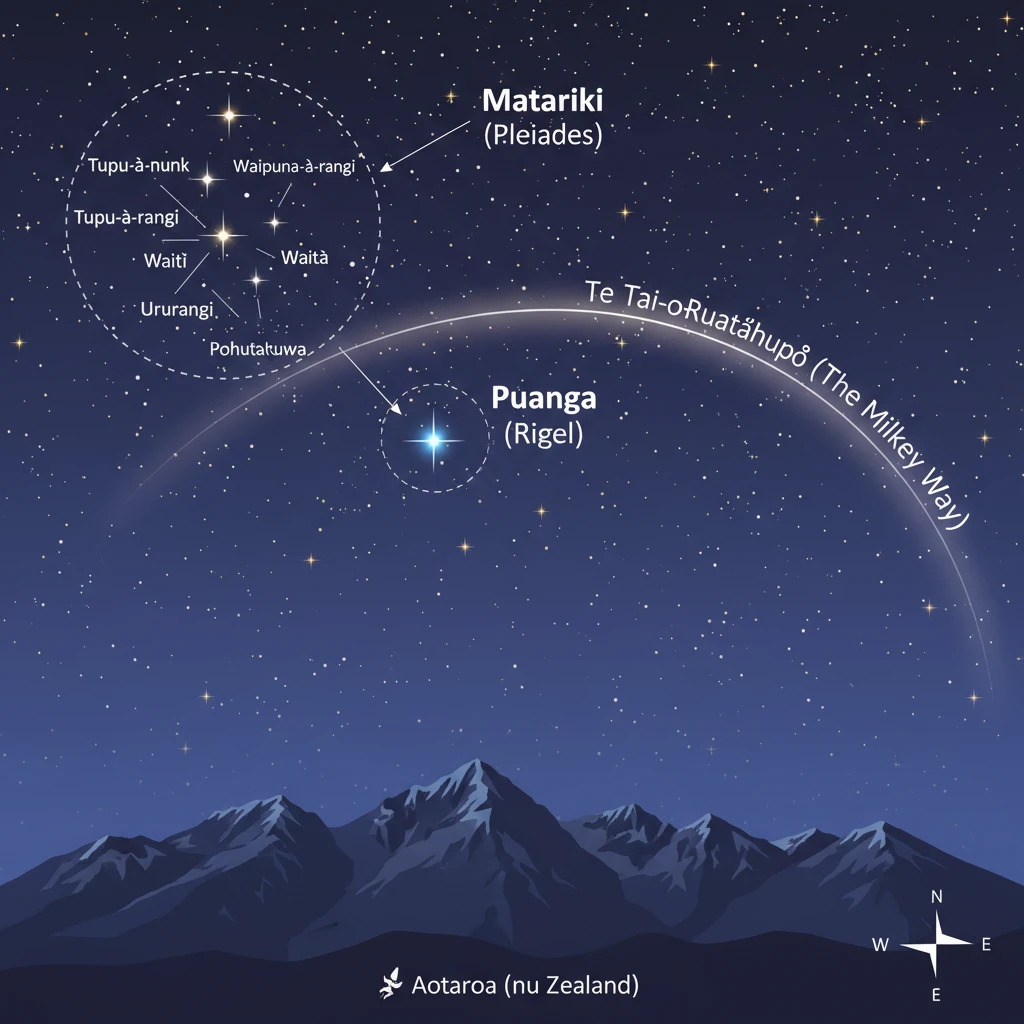

Decoding the Nine Stars: Beyond the Seven Sisters

For many years, under the influence of Greek mythology which refers to the Pleiades as the “Seven Sisters,” it was commonly taught in New Zealand that Matariki consisted of seven stars. However, a deeper dive into authentic Māori manuscripts and the work of modern scholars reveals that many iwi recognize nine distinct stars in the cluster. Each star holds dominion over a specific aspect of the environment and human life.

Understanding these domains is essential for an adult perspective on the holiday, as it shifts the focus from myth to environmental stewardship:

- Matariki: The mother star who signifies reflection, hope, and the health of the people. She gathers the others to bring good fortune.

- Pōhutukawa: Connects Matariki to the dead. This star carries the spirits of those who have passed away in the previous year up to the heavens. It is the reason Matariki is a time of remembrance.

- Tupu-ā-nuku: Associated with food that grows within the soil (kumara, potatoes).

- Tupu-ā-rangi: Associated with food that grows above ground (birds, fruit, berries).

- Waitī: Tied to fresh water bodies and the food sources within them (eels, trout).

- Waitā: Represents the ocean and salt water food sources.

- Waipuna-ā-rangi: Associated with the rain.

- Ururangi: Associated with the winds.

- Hiwa-i-te-rangi: The wishing star. This is the star to which you send your dreams and aspirations for the coming year.

This nine-star system represents a holistic view of the ecosystem. The brightness of Waitī, for example, might predict the health of the rivers for the coming season. If Waipuna-ā-rangi was obscured, it might foretell a drought.

Regional Variations: The Significance of Puanga

A sophisticated understanding of the Matariki origin story for adults requires acknowledging that Matariki is not the universal New Year signal for all Māori. New Zealand’s geography creates significant variations in astronomical observation.

Why do some Iwi celebrate Puanga instead?

For tribes located in the Far North, Taranaki, Whanganui, and parts of the West Coast of the South Island, the Matariki cluster is often obscured by mountain ranges or is too low on the horizon to be seen clearly during the mid-winter months. For these iwi, the star Puanga (Rigel), the brightest star in the constellation Orion, is the herald of the New Year.

Puanga usually rises slightly before Matariki. The variation highlights the tribal autonomy (tino rangatiratanga) inherent in Māori culture. It is not a “disagreement” on the mythology, but an adaptation to the physical landscape. While the government has standardized the “Matariki” public holiday, the cultural reality is a dual celebration of Matariki and Puanga, depending on one’s whakapapa (ancestry) and rohe (region).

Academic Perspectives and the 21st Century Revival

The resurgence of Matariki in the 21st century is not an accident; it is the result of dedicated academic research and a cultural renaissance. For much of the 20th century, the celebration of Matariki had dwindled, largely replaced by colonial holidays and the Gregorian calendar.

The pivotal figure in the modern understanding of the Matariki origin story is Dr. Rangi Matamua, a professor of Māori astronomy. His work is largely based on a 400-page manuscript written by his ancestor, Te Kōkōrangi, in the late 19th century. This manuscript contained detailed knowledge of the stars, their meanings, and the ceremonies associated with them, which had been safeguarded within his family for generations.

Dr. Matamua’s academic work challenged the simplified “Seven Sisters” narrative and reintroduced the nine-star constellation to the general public. This academic rigor provided the foundation for the New Zealand government to declare Matariki an official public holiday starting in 2022. It marked a significant shift: the first public holiday in New Zealand centered on indigenous knowledge rather than colonial history or religious observance.

The Maramataka: Indigenous Timekeeping Science

Adults diving into the origins of Matariki must understand the Maramataka—the Māori lunar calendar. Unlike the solar Gregorian calendar which is fixed, the Maramataka is observational and fluid. It relies on the phases of the moon and the position of stars.

Matariki does not happen on the same date every year in the Gregorian calendar. It occurs during the lunar phase of Tangaroa (the last quarter moon) of the lunar month Pipiri (June/July). This intersection of the lunar phase and the stellar rising is what determines the exact date of the holiday.

This system of timekeeping is incredibly sophisticated. It aligns human activity—planting, fishing, resting—with the natural energy levels of the environment. The revival of Matariki is, therefore, also a revival of living in sync with the environment, a concept that resonates deeply in the modern era of climate change awareness.

Conclusion

The Matariki origin story for adults is a tapestry woven from grief, astronomy, geography, and resilience. It moves beyond the simple myth of star-children to reveal a complex understanding of the cosmos. Whether viewed as the eyes of Tāwhirimātea or as a meteorological forecasting tool, Matariki represents a time for New Zealanders to stop, reflect on those lost, and plan for the future with an indigenous perspective that honors the earth and sky.

Why does Matariki have 9 stars instead of 7?

While the Greek Pleiades tradition cites seven stars, Māori astronomy identifies nine. The two additional stars, Pōhutukawa and Hiwa-i-te-rangi, are crucial to the Māori worldview, representing the connection to the deceased and the aspirations for the future, respectively. The visibility of nine stars was often a test of excellent eyesight and atmospheric clarity.

Is Matariki the same as the Pleiades?

Yes, astronomically, Matariki is the open star cluster Messier 45 (M45), known in the West as the Pleiades. However, culturally, Matariki encompasses specific narratives, environmental indicators, and spiritual meanings unique to Māori culture that differ from the Greek or Japanese (Subaru) interpretations.

What is the difference between Matariki and Puanga?

Matariki is the star cluster Pleiades, while Puanga is the star Rigel in Orion. Iwi in the Far North and West Coast celebrate the New Year upon the rising of Puanga because their view of Matariki is often obstructed by geography. Both signal the New Year but are used by different tribes.

How did Māori use Matariki to predict the weather?

Tohunga (experts) observed the color, brightness, and distance between the stars in the cluster. Blurry or hazy stars indicated a wet, cold season affecting crops, while clear, bright stars predicted a warm, abundant season. Each individual star in the cluster corresponded to a specific environmental domain (e.g., wind, rain, ocean).

When is the best time to view Matariki?

Matariki is best viewed in the early morning, just before dawn, typically between late June and mid-July. You should look towards the northeastern horizon. The cluster appears low in the sky before the sun rises.

What are the three main principles of Matariki?

Modern celebrations focus on three principles: Remembrance (honoring those who have passed), Celebrating the Present (gathering with whānau and sharing food), and Looking to the Future (planning and setting intentions/wishes for the year ahead).