Waitī and Waitā are two distinct stars within the Matariki cluster (Pleiades) representing the essential balance of water. Waitī watches over all freshwater bodies, including rivers, lakes, and springs, and the creatures within them like eels. Waitā watches over the ocean, tides, and salt water marine life, symbolizing our connection to the vast seas.

What are the Waitī and Waitā Stars?

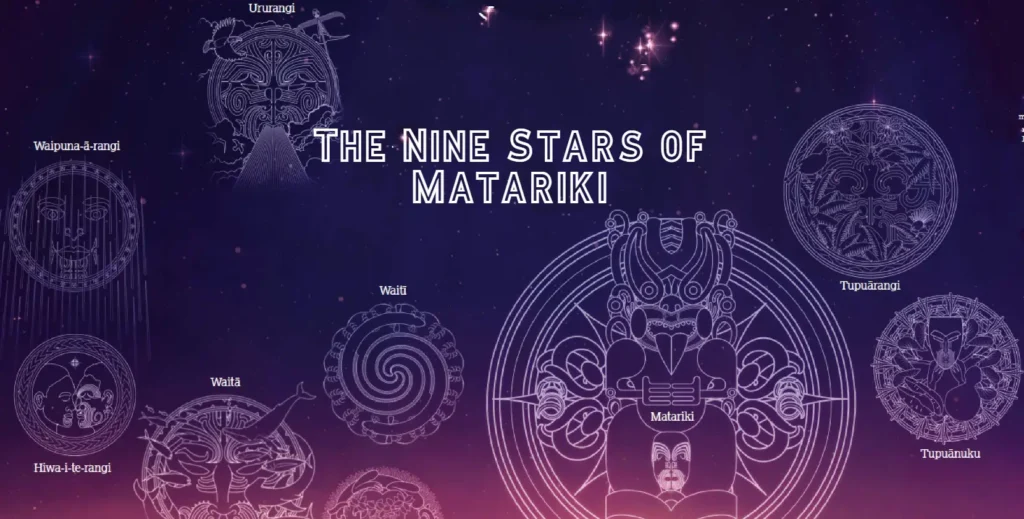

In the constellation of Matariki (the Pleiades), which signals the Māori New Year, each star holds a specific dominion and purpose. While Matariki is the mother star surrounded by her daughters, two of these stars form a unique pair dedicated entirely to the hydrosphere. These are the Waitī and Waitā stars. Their positioning in the sky and their brightness have historically served as critical indicators for environmental health and food availability for the coming year.

Understanding these stars requires viewing the environment as an interconnected system. Water flows from the mountains, through the rivers (Waitī), and eventually mixes with the vast ocean (Waitā). This journey of water mirrors the relationship between these two stars. They sit close to one another in the cluster, reminding observers that while fresh water and salt water are distinct, they are inextricably linked in the cycle of life.

For modern observers, these stars are more than just celestial bodies; they are symbols of our ecological duty. As we celebrate Matariki, acknowledging Waitī and Waitā transforms the holiday, which includes Whakamahara: Remembering Loved Ones, from a mere observation of the sky into a call to action for water conservation and guardianship.

Waitī: The Star of Fresh Water

Waitī is the star connected to fresh water and all the life that sustains itself within it. The name itself can be translated to mean “sweet water” or “fresh water.” In Māori mythology and astronomy, this star creates a direct link to the health of rivers (awa), lakes (roto), streams, and springs (puna). It is the celestial guardian of the hydrological cycle on land.

The Domain of Waitī

When tohunga (experts) looked to Waitī during the rising of Matariki in mid-winter, they were not just looking at a point of light; they were assessing the mauri (life force) of the freshwater systems. If Waitī appeared bright and clear, it was a tohu (sign) that the water systems were healthy, the melting snows would feed the rivers adequately, and the freshwater food sources would be abundant. Conversely, a hazy or shimmering appearance warned of potential droughts or a scarcity of freshwater kai (food).

Biodiversity: The Tuna (Eel) Connection

Waitī is inextricably linked to the creatures that inhabit fresh water, most notably the tuna (longfin and shortfin eels), kōura (freshwater crayfish), and various species of native fish like kōkopu and inanga (whitebait). The lifecycle of the tuna, in particular, is a marvel of nature that Waitī oversees. These creatures migrate from the inland waterways out to the deep ocean trenches near Tonga to breed and die, with their larvae drifting back to New Zealand to restart the cycle.

Today, Waitī serves as a reminder of the fragility of these ecosystems. With the decline of the longfin eel population and the pollution of waterways, this star asks us to examine our impact on the rivers. Are the nitrates from farming affecting the water quality? Is urban runoff polluting the habitats of the kōkopu? Celebrating Waitī means acknowledging these challenges and working to restore the “sweetness” of the water.

Waitā: The Star of Salt Water

Beside Waitī sits Waitā, the star associated with the ocean and the diverse life it holds. Waitā represents Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa (the Pacific Ocean) and is often associated with the vastness of the sea, the tides, and the currents. The name essentially translates to “salt water.” This star acknowledges the significance of the ocean not just as a food basket, but as the highway of the ancestors who navigated the Pacific to reach Aotearoa.

The Bounty of the Ocean

Waitā is the guardian of kaimoana (seafood). This includes deep-sea fish like hāpuku and snapper (tāmure), as well as coastal resources like mussels (kūtai), paua, and crayfish (kōura), all of which could feature in a Traditional Hāngī Guide. In traditional times, the clarity of Waitā predicted the success of the fishing season. A clear, distinct Waitā signaled that the currents would be favorable and the harvest plentiful. A dim Waitā suggested that the ocean might be turbulent or that fish stocks would be low, prompting tribes to conserve their resources or rely more heavily on land-based crops.

Ocean Currents and Climate

Beyond food, Waitā is connected to the physical behavior of the ocean. It represents the currents that regulate the climate. Māori navigators understood the ocean’s language—the swells, the temperature, and the drift. Waitā embodies this knowledge. In a modern context, Waitā is increasingly relevant to discussions about rising sea levels, ocean acidification, and the health of coral reefs and marine kelp forests.

The pairing of Waitī and Waitā emphasizes the mixing zone—estuaries and river mouths—where fresh water meets salt. These brackish environments are often the nurseries for many marine species, further highlighting why these two stars appear side-by-side in the night sky.

Bio-indicators: Reading the Stars for Harvest

One of the most sophisticated aspects of Māori astronomy is the use of stars as bio-indicators. The Waitī and Waitā stars act as an early warning system for ecological health. This is not superstition; it is observation based on centuries of data collection regarding atmospheric conditions.

The Science of Atmospheric Distortion

When we talk about the “brightness” or “haziness” of a star, we are often describing atmospheric turbulence and moisture content in the upper atmosphere. The rising of Matariki occurs in mid-winter (June/July). The visibility of the stars at this specific time is affected by the thermal layers in the air.

- Clear, Bright Stars: Indicate stable atmospheric conditions, often correlating with predictable weather patterns conducive to breeding and migration of fish species.

- Hazy, Shimmering Stars: Indicate atmospheric instability, high moisture, or turbulence, often preceding erratic weather, storms, or warmer/colder than average seasons which can disrupt the spawning cycles of eels or the migration of ocean fish.

Salmon, Eels, and Migration

While salmon are an introduced species, the principles of Waitī apply to them as they move from fresh to salt water. However, for the indigenous eel (tuna), the connection is vital. The stars signaled when the tuna heke (eel migration) would likely occur. If Waitī was bright, it was a good omen for the trapping season. If the stars appeared “closely huddled” or blurry, it suggested a need for strict rāhui (temporary ritual prohibition) to allow stocks to recover.

Kaitiakitanga: Environmental Responsibility

The concept of Kaitiakitanga refers to guardianship, stewardship, and protection. It is perhaps the most critical lesson we can learn from the Waitī and Waitā stars. In the context of Matariki, these stars are not passive observers; they are active reminders of our duty to the environment.

Te Mana o te Wai

In New Zealand, the concept of “Te Mana o te Wai” (the mana of the water) is now embedded in legislation and planning. It prioritizes the health of the water body first, the health of the people second, and commercial interests third. This aligns perfectly with the celestial hierarchy of Waitī and Waitā. If the water is not healthy (if the star is dim), the people cannot thrive.

Kaitiakitanga involves practical steps to ensure the mauri of the water is sustained for future generations. This includes:

- Riparian Planting: Planting natives along riverbanks to stop sediment runoff (protecting Waitī).

- Reducing Plastic Waste: preventing plastics from entering storm drains and ending up in the ocean (protecting Waitā).

- Sustainable Fishing: Adhering to catch limits and respecting marine reserves.

Celebrating Through Action: Activities and Conservation

Matariki is a time for celebration, but also a time for planning and work. To honor Waitī and Waitā, families, schools, and communities can engage in specific activities during June and July that connect them to the water.

Exploring Local Waterways

To truly understand Waitī, you must know your local water source. An excellent activity for Matariki is to trace the path of your local stream.

- Stream Mapping: Find the nearest stream to your home. Use a map to trace where it starts and where it ends. Does it flow into a larger river? Does it reach the sea?

- Water Testing: Many regional councils offer citizen science kits to test water clarity and pH levels. This is a practical way to “read” the health of the water, much like the tohunga read the stars.

- Spotlighting for Eels: Visit a local stream at night with a red-light torch. You may spot native eels or kōkopu active in the dark. This connects you directly to the creatures of Waitī.

Conservation Projects to Join in June/July

Winter is the prime planting season in New Zealand, making Matariki the perfect time for restoration work.

- Beach Clean-ups: Honoring Waitā by removing debris from the coastline. Even if you live inland, cleaning up local parks prevents rubbish from washing into stormwater drains that feed the ocean.

- Wetland Restoration: Wetlands are the kidneys of the earth, filtering water before it reaches the sea. Many community groups host planting days in June and July to restore these vital ecosystems.

- Support ‘Million Metres Streams’: This is a project dedicated to riparian planting across New Zealand. Donating or volunteering helps restore the banks of waterways, directly serving the purpose of Waitī.

By engaging in these activities, we move beyond the theoretical appreciation of the Waitī and Waitā stars and embody the spirit of the stars themselves. We become the guardians on earth that the stars represent in the sky.

Where can I find the Waitī and Waitā stars in the sky?

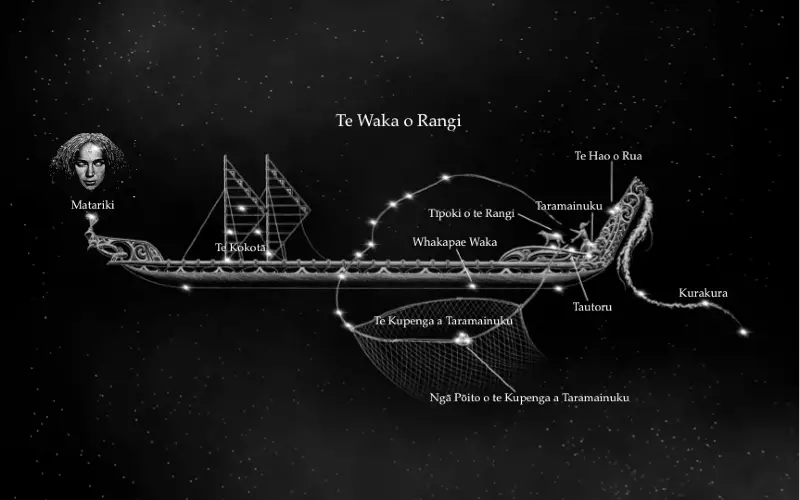

Waitī and Waitā are part of the Matariki cluster (Pleiades). They are located below the central star, Matariki. You can also use an Interactive Night Sky Map Tool: Locate Matariki Now to pinpoint them. Waitī is typically positioned slightly higher than Waitā. To find them, locate the three stars of Orion’s Belt, follow the line to the left to find the bright star Tautoru, and continue to the cluster of tiny stars that is Matariki. Waitī and Waitā are the two stars on the bottom right of the main group.

How do you pronounce Waitī and Waitā?

Waitī is pronounced “Why-tee” (with a long ‘e’ sound at the end). Waitā is pronounced “Why-tah” (with a long ‘a’ sound at the end). The macron indicates a lengthened vowel sound.

What happens if these stars appear hazy during Matariki?

Traditionally, if Waitī or Waitā appeared hazy, shimmering, or dim upon the rising of Matariki, it was considered a bad omen for the year ahead. It predicted a shortage of food from the water (freshwater or ocean respectively) or difficult weather conditions that would make fishing dangerous or unproductive.

Can I see Waitī and Waitā without a telescope?

Yes, the Matariki cluster is visible to the naked eye, though it appears as a tight group of light. People with very sharp eyesight can distinguish individual stars like Waitī and Waitā. However, using binoculars makes it much easier to separate the individual stars within the cluster.

Why are eels (tuna) associated with Waitī?

Eels are the apex predators of New Zealand’s freshwater systems and a critical traditional food source for Māori. Because Waitī is the guardian of fresh water, the health and abundance of the eel population are directly spiritually and physically linked to this star.

What is the difference between Waitī and Waitā?

The primary difference is the type of water they represent. Waitī represents fresh water (rivers, lakes, springs) and freshwater biodiversity. Waitā represents salt water (oceans, seas) and marine biodiversity. Together they cover the entire hydrological cycle.